Books and Vintage Merchandise Store

The book has picturesque details of the First World War, enough to compete with any documentary out there and “Win!”

Information from manuscripts and authentic libraries and sources that are impossible to find these days.

Pictures that are rare and extinct by popular opinion or has the significance enough to belong to a museum.

Yet another unique facet of Book of the Century is its singular attention to the role of women in the events which culminated in the conflict. The Great War is usually told as a struggle populated almost entirely by men.

While it is true few women fought in the trenches, the activities of women had major effects on the evolution of the war and the political dramas which preceded it. Their various jobs, positions, and personalities—to say nothing of their behind-the-scenes impact upon political developments—were markedly instrumental well before Archduke Franz Ferdinand was shot to death in 1914.

One more facet differentiating Book of the Century from all other histories of the First World War is its freedom to take detours which in themselves are interesting g but whose relevance to the main topic may not, at first, Be obvious. For example, one of the symbols of WWI which marks it in the public imagination is barbed wire.

Book of the Century, because it is available only online, can spend some time explaining how a modest, little-known piece of federal legislation enacted by Abraham Lincoln to encourage settlers (to move to the American mid-west), led to the invention of a string of steel with painful barbs on it. Barbed wire proved itself so efficacious so quickly that its biggest maker soon grew into the conglomerate we know today as U.S. Steel. Tens of thousands of miles of barbed wire were unspooled on the Western Front alone. These coils led to the deaths of myriads of soldiers—that much is known. Few know, however, that barbed wire was the first killer app of modern agriculture.

An immense 7000+ Pages and still counting. A history of everything that shaped today’s modern world from where we were around 1800’s is the main content of my book.

Despite its current length and thorough treatment of the century leading to World War One, Book of the Century is only about 80% finished. Greg had to put the book on the back burner so that he could develop this website and complete the research and writing of Authorized Images.

It grew out of my frustration with histories of World War One which did not go far back enough in time to describe the people and explain the events which led to what became known as the Great War.

Moreover, so many of the histories of the conflict annoyingly assumed that the reader was intimate with the geography of battlefields, or how armed forces were organized, or how weapons were developed.

Greg wanted to read a book that could throw light on the background to the war (for example, elucidate why France and Germany seemed to relish their feuding) while able to offer sidebars and detours on topics which, while at first glance having nothing to do with the war, did indeed have influence on the conduct of the conflict. He also wanted this idea book to be heavily illustrated so that you could see what places and people mentioned in the text looked like. Not able to find such a book, he decided to write it himself, buttressing the text written in plain accessible English with thousands of images and maps never before seen in any history of the approximately 100 years with which he deals in this book.

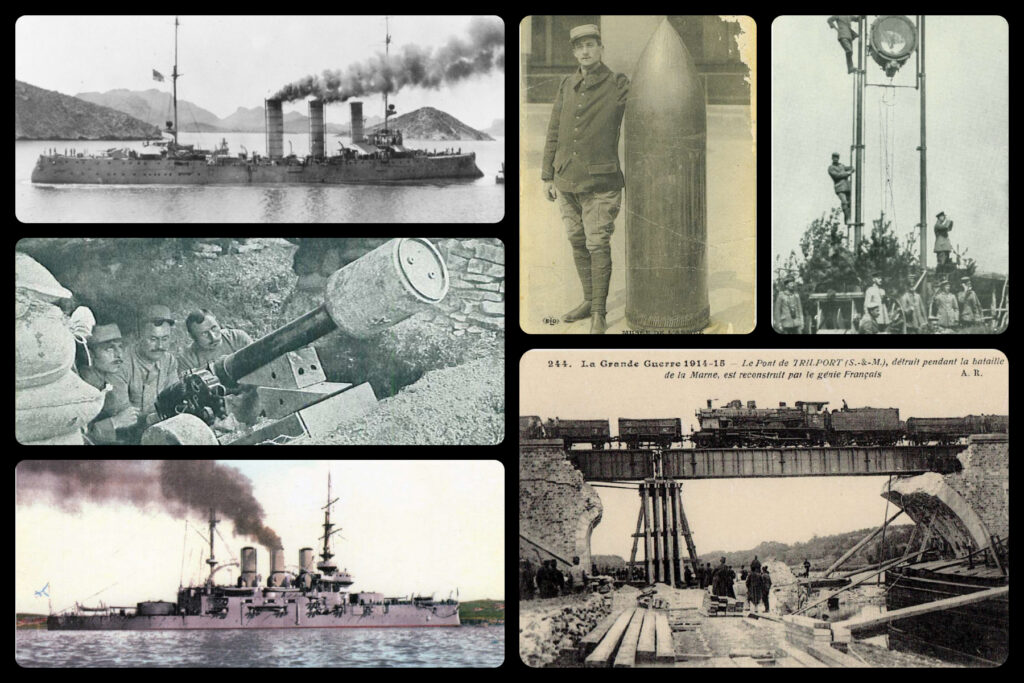

My book depicts the lives of Generals and Commanders whose fight and leaderships changed the course of history through battle.

How they came into the fight and what decisions they took under what circumstances.

Their social lives, their personal lives, everything in details get portrayed in my book.

Sometimes even famous last words or even detailed commands in battles of various commanders, colonels and generals appear in my book at frequent intervals.

Please find some glimpses of them in my blog

Even though Men, Generals and Warriors are what we visualize when it came to battlefields of World War I.

WWI isn’t just about the battle.

But whatever happened before and led to it.

And given the socio-political platforms and events that brought the War into being, women played as much role as the men.

They just didn’t seem to appear as often as they should have, in most of the history books out there.

My book enthusiastically describes the role of women in the various aspects of the society from around the world.

How women of various status or class helped change the course of history without us knowing is one of my favourite things from my book.

Some examples are sought over in my Blog.

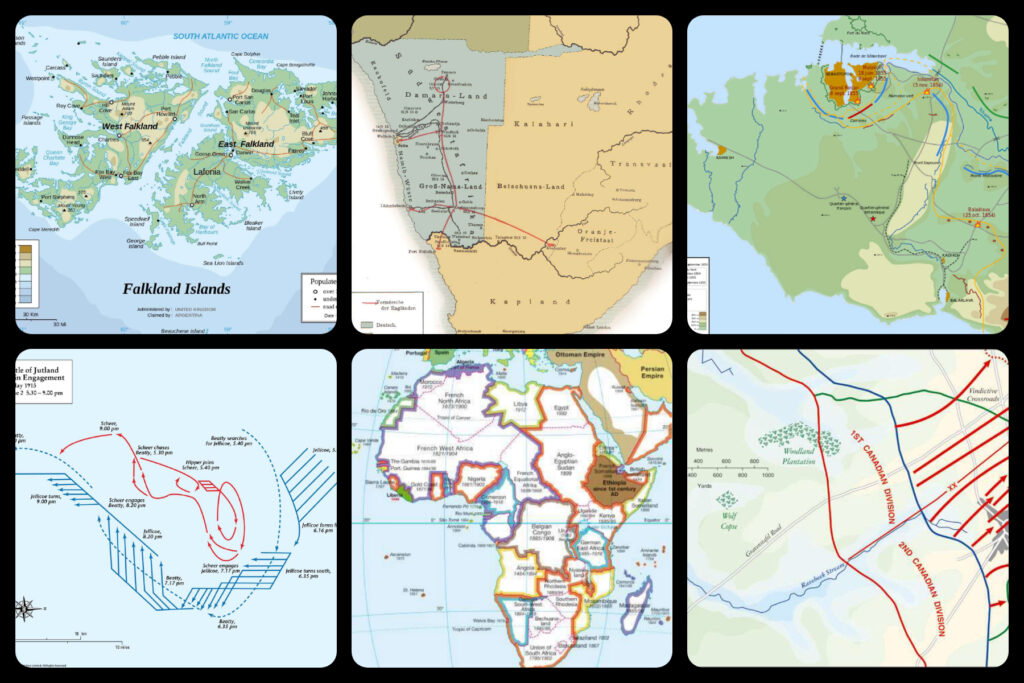

You will come across beautiful Maps with battle movements and maps from ancient historical places that don’t exist anymore.

My maps depict places where borders were too different from the modern day ones.

Also if you are interested, feel free to grab an opportunity to design these maps through a paid internship program for my Book.

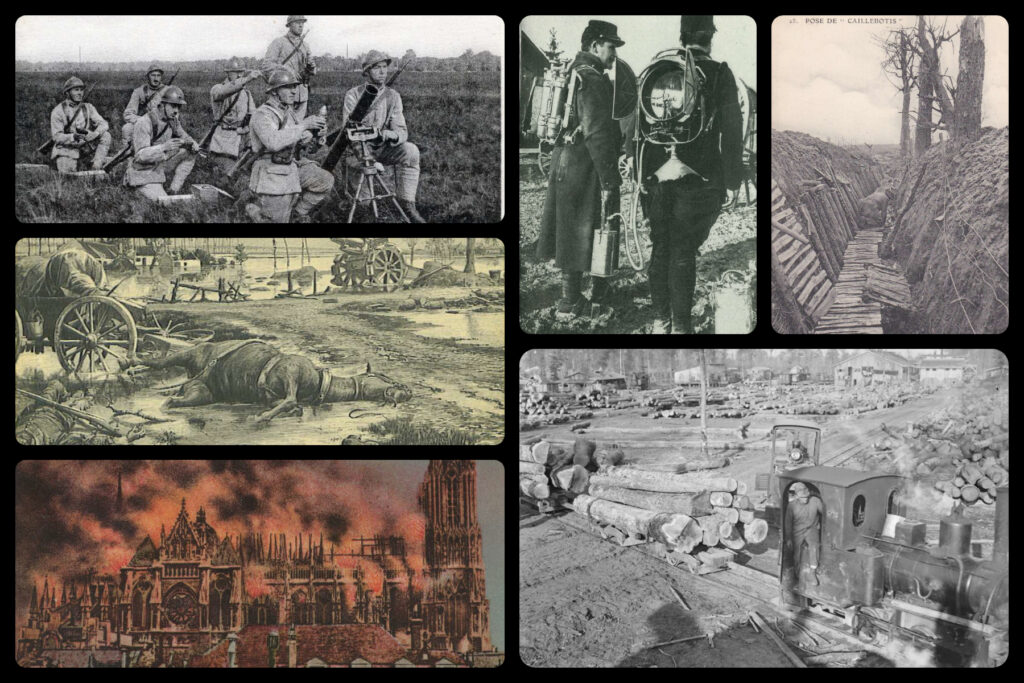

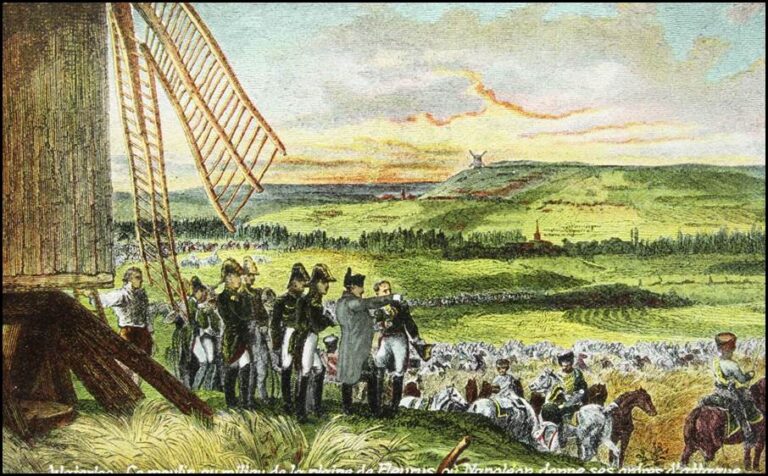

Glimpses of battles, social events, unique battlefield moments and war events caught in cameras or from some vantage point frequently appear with lively pictures in my book.

However hard it may be to sort out and mention the numerous such events that happened during WWI or led to it, I try my best to bring them together in my book. Some glimpses are mentioned here.

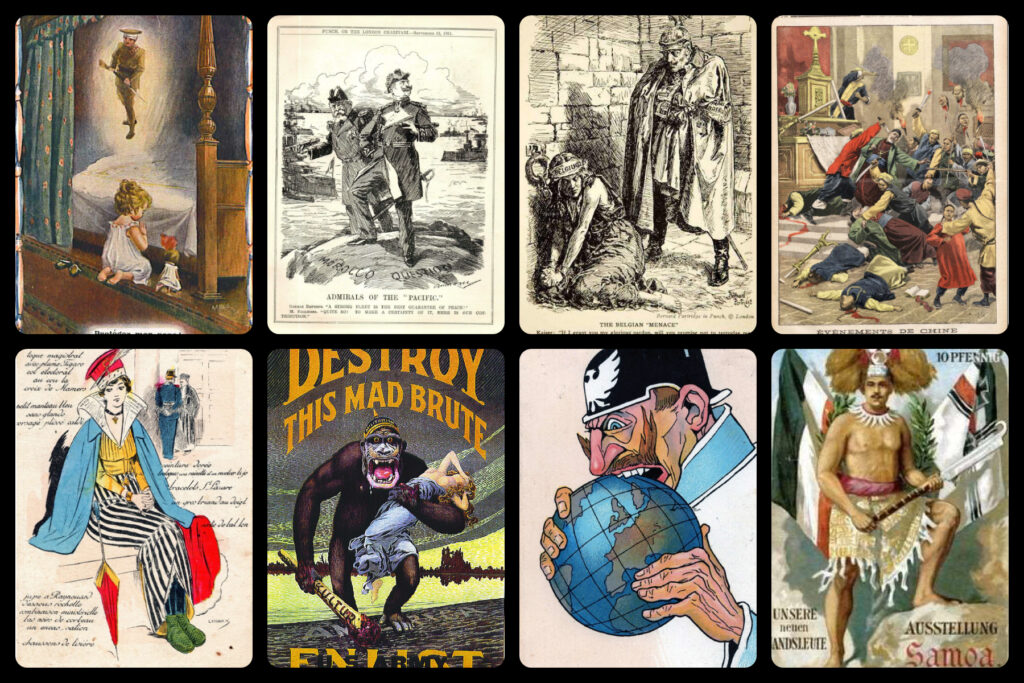

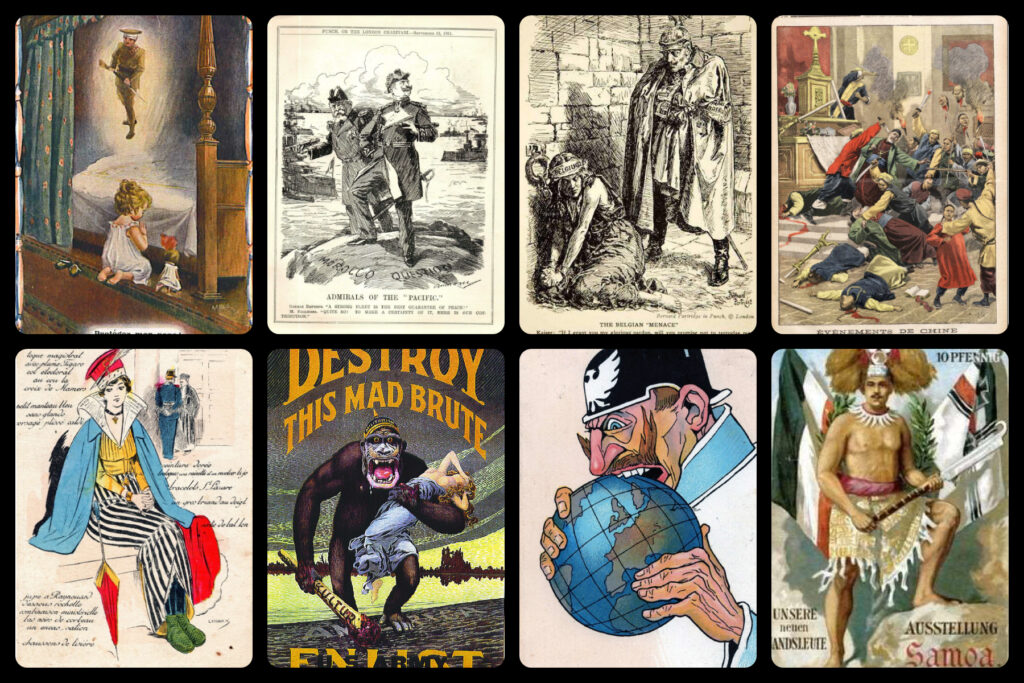

Illustrations and Comic arts were the best means to enforce propaganda or influence the public during the war or before 1914.

And if you cannot influence the public, who are hungry for knowledge about what’s going on out there, how will you get anything so impossible done? Such was the concern of every media platform during and before World War I.

Society didn’t have any other means but newspaper, newsreels and propaganda flyers to quench their thirst for news of World politics and battlefields.

My book depicts all that happened behind and in front of all the propaganda posters or comic arts, and how they moulded the mind of the society.

Almost each and every page has a picture along with entertaining story. If you want more idea on how frequently relevant historic pictures appear in my story please check out a broader view of my History book in the making here.

Here are a few glimpses of pages from my Book. It shows how each image is flaunted by descriptive and vivid captions. As you can imagine it is very difficult to divulge every topic that is discussed in my book, I will try to give you some idea, just to help you out.

After that famous fight, Europe experienced approximately a century of peace, a period interrupted only by occasional—and very brief–fighting between neighbouring nations. Of course, essential to this tale is the rise of the United States and Japan as Great Powers.

Having given an entertaining and detailed history of many of the people and events who shaped European politics in the years leading to WWI, Gatenby then offers an account of the Great War itself—a telling which excludes the minutiae of standard military accounts in lieu of concentrating on the key elements which led to advances and setbacks for both sides.

And to help the reader comprehend the gigantic cast of characters and the many geographical sites important to the story, Book of the Century suavely incorporates the results of his unique access to a massive private archive of images previously unavailable to historians.

These pictures, of which there are thousands throughout the book, make it so much easier for readers to follow the evolution of the First World War (and its resolution) while simultaneously delighting the eye with antique images, often beautiful to behold, never seen before in any other book-length treatment of the war.

Gatenby’s history is also extraordinary in highlighting two facets of history rarely mentioned in most history books addressing the Victorian era and WWI: the importance of women and their powerful influence throughout this hundred-year period, and the singular role of brilliant engineering in improving the capacity of railways, ships, motors, aircraft, and weapons which made the Great War so costly in blood and treasure.

There has never been a book of this immensity which so successfully treats so many topics in such an accessible, indeed, intriguing and inviting manner. It is not just another history book. It is The Book of the Century.

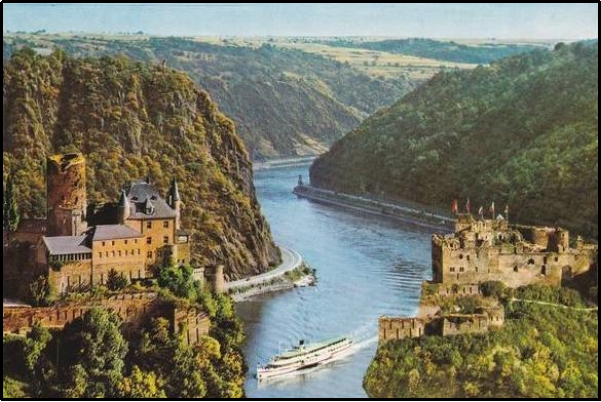

The tale of Lorelei may have its origins in the difficulties sailors have always faced from the sharp bends in the Rhine, especially through the Lorelei Gorge (as seen above).

The unpredictable but always strong currents make for treacherous steering. Since about 1880, tourists have travelled the scenic, castle-laden portions of the river in comfortable steamboats, originally driven by paddle wheels.

Lady Jane Digby, in 1828 offering a daring amount of décolleté and a saucy look in a watercolour by James Holmes (1777–1860).

Holmes in his lifetime was well-known in the UK for his portraits. He made two likenesses of Lord Byron which achieved wide currency when they were published as engravings and were sold throughout the Anglosphere.

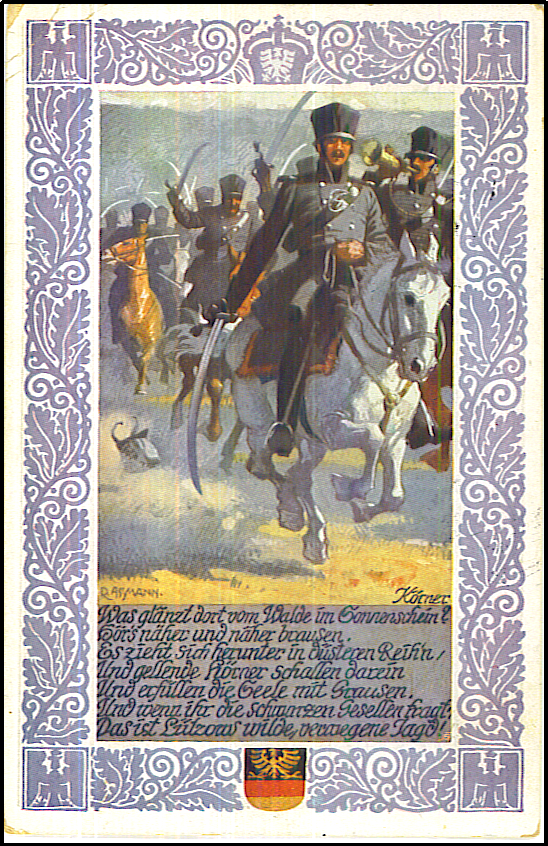

From the inception of the picture postcard in the 1890s until the start of the Second World War, Theodor Körner was a popular subject for tourists and for postcard collectors. Both German examples above date to about 1905.

Interior of the Walhalla near Regensburg, Bavaria. The edifice harbours busts, plaques, and statues celebrating hundreds of German-speaking heroes, covering a two-thousand-year period.

When the building opened in 1842, it contained commemorations of 150 people, including authors, philosophers, scientists, composers, visual artists, notable monarchs, religious leaders, and, inevitably, military commanders.

Not everyone honoured in this Teutonic Hall of Fame is, in fact, famous. One of the most recent additions, for example, is a plaque honouring Sophie Scholl, a Munich student and resistance leader, executed in 1943 by the Nazis.

A postcard issued by the German Red Cross during the first weeks of the Great War, featuring a beefy German officer protecting the German side of the Rhine River. The card celebrates the patriotic song “Die Wacht am Rhein” [The Watch on the Rhine]. The margin at left quotes a few words from the lyrics.

A few lines from The Watch on the Rhine will give a taste of the unabashed patriotism aroused in the German breast by the 19th c. French threat of annexation of the Rhineland:

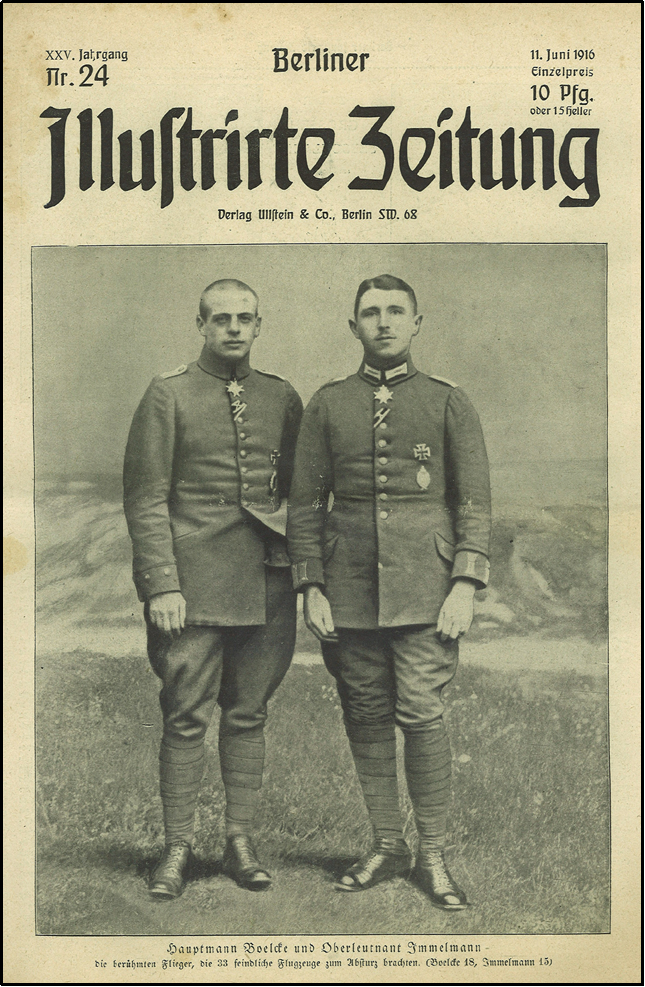

Until 1916, the Pour le Mérite was made with gold. However, in the middle of WWI the Germans were short of hard currency acceptable to inhternational bankes, so needed to retrieve all the gold they could from whatever source.

Kaiser Wilhelm II signed a decree in 1916 insisting that all German medals thereafter used silver gilt rather than gold. By the end of the Great War just under 700 members of the armed forces had won the Pour le Mérite.

Above, Oswald Boelcke (left) and Max Immelmann, two of the most famous German aces of World War One, portrayed wearing the “Pour le Mérite” above the top button of their jackets. It was regulation that, when in uniform, an officer must always wear the coveted honour in public.

These two men were the first pilots and the first junior officers ever to receive the award. Max Immelmann was shot down and killed (aged twenty-five) a mere week after this magazine appeared on newsstands. Immelmann was the supreme inventor of German fighter tactics early in the War.

( More details of their war effort in the Book)

The Pour le Mérite was awarded less than 700 times throughout the Great War. It was discontinued as a medal after the Armistice of 1918.

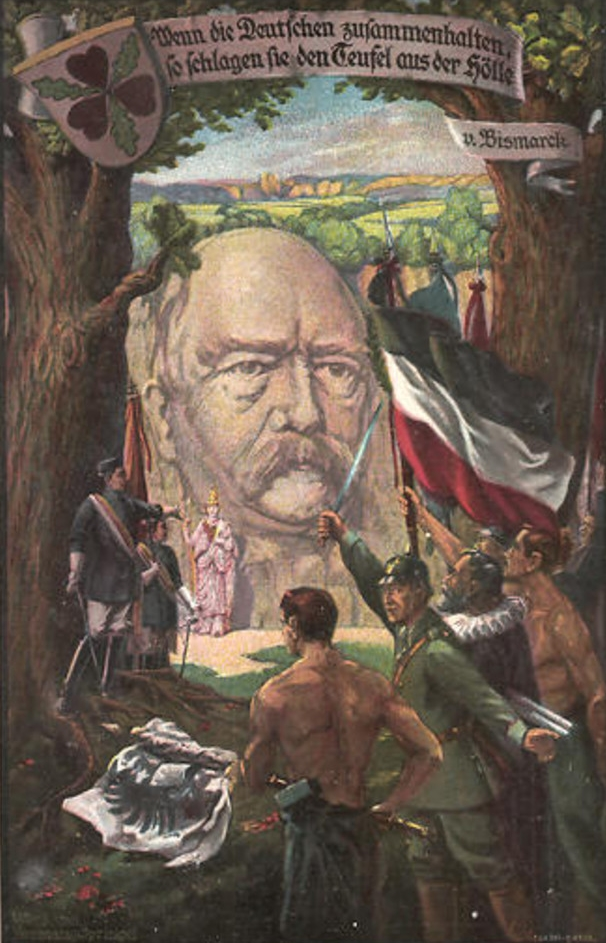

In the years 1900 to 1914, when adulatory postcards such as this were published in the millions in Germany, there seemed no limit to how much one could associate Bismarck with ultra-nationalist pride and glory in the military.

If you want to read a sample chapter from my book before it gets released. Here’s a copy you can buy now.

In the late 1990s I began to do research for a novel centred on two young Americans, later to become world famous, who were both living in Toronto in 1918—indeed, lived only 500 meters apart. William Faulkner, the great novelist (and winner of the Nobel Prize) moved to Toronto to join the Canadian air force.

Amelia Earhart, the renowned female aviator, moved to Toronto at the same time to join a nursing organisation devoted to helping the seriously wounded recently shipped home from the Western Front. The novel was going to presume they met at a dance and, two Americans in a foreign land, had become (possibly flirtatious) pals.

My interest in History began well before I started to travel around the globe. Indeed, it was my interest in history (originally to better understand Literature and Visual Art), which propelled me to delve into so much geography.

From those queries it was an inevitable step to become voracious in seeking more knowledge about political, diplomatic, social, and military history, first as it related to the writers, painters, and composers I admired, and then quickly onto the wider world.

However, the more history books I devoured, the more questions arose within me. To my frustration, too many of the tomes I read assumed the reader already possessed extensive knowledge of the subject, had a foundational grasp which, when I began, I did not have.

For example, a military historian might write something skin to this: “had the general sent two more battalions into the battle he could have avoided another Sedan.” Such a sentence assumes the reader knows how many soldiers comprise a battalion, assumes he or she knows why two and not, let us say, one battalion, and assumes the reader understand what Sedan is or was.

After reading too many books of this ilk, I decided to write a different kind of history book, one which assumes the reader is ignorant of certain facts but is well-intentioned enough to want to learn when those facts are delivered in an accessible, adult manner.

Too many of the history books which were my daily fare for two decades also seemed so obsessed with telling how the 8th Regiment moved a meter to the left on Monday and then two meters to the right on Tuesday that they became indifferent to the human side of politics and war, particularly the part played by women in the build up to these conflicts as well as the roles they embraced when fighting was underway.

With unpleasantly regularity, books about literary authors and about military history both struck me as deficient in offering pictures of what life was like at the time the principals were alive.

My discovery of the colossal world of antique postcards opened my eyes to what destruction of a village by artillery could mean as American publishers especially were given nearly unlimited access to the front lines as the Allied side and the side of the Central Powers strove to let the neutral Americans illustrate the nobility of their soldiers and the evils of the enemy.

Yet, too often, it seemed that the authors of military histories gave their graduate students a list of photos needed of commanders and politicians, sent them to the relevant national war museum, with the result that the resulting texts tended to have the same photos year after year—many of the pictures being studio portraits inf full dress uniform or images taken long after battles were fought.

Finally, I should note that far too many maps in history texts are indecipherable to the lay reader. Such maps may contain gargantuan amounts of information to those who know what all the acronyms and symbols mean, but they are overloaded and overburdened as far as non-specialists are concerned.

I wanted a book with lots of maps (why should anyone outside France know where Sedan is?) which are easy to read and are informative of the adjoining text.

In 1998 I began my concentrated study of the First World War (in addition to the Victorian and Edwardian eras which provided the kindling and fuel for that conflict).

My research necessarily involved reading a lot about the First World War.

I quickly discovered that the relevant histories assumed the reader already possessed immense knowledge of 19th c. events in Europe and had plenty of knowledge about how armies functioned.

For example, these books were fond of sentences such as “had the general only thrown two more brigades into the battle the battle would have been won.” Such lines left me scratching my head feeling ignorant.

I was forced to ask:

“How big is a brigade? What is the difference between a battalion and a brigade?”

In fact, having never served in the army, I soon realized I knew next to nothing about how the military worked just before and during a war.

Yet none of the hundreds of war histories I read at that time supplied the information I needed in a way that was easy to find and grasp.

The military and political histories also made constant reference to battles and places completely unknown to me—but which the authors assumed their readers must know.

“They wanted to avoid another Sedan” was a typical sentence.

Well, I knew the historian was not referring to a kind of car but to just what he was referring and why it was important was always assumed, never explained.

Also, there were constant remarks about Galicia, Posen, Carpathia, Pomerania and the like—always cited as if any civilized person would know immediately where those places were on a map and how their pasts were obvious influences on WWI.

Furthermore, I found too many of the books were filled with minutiae about specific battles of little or no interest to the lay reader.

While knowing that the 40th, 53rd, and 78th regiments fought in such-and-such a battle is important to those who fought in a conflict, I believe the average reader today only wants to know which national army was involved.

You don’t need to know that the 17th battalion moved four meters to the left on Monday and then six meters to the right on Tuesday.

That said, sometimes it is helpful to learn how many soldiers were casualties. Compared to what had happened in previous wars, the numbers killed or wounded in WWI were unbelievably huge. Even reading the figures today the reader can be forgiven for thinking there must be typographical errors in the description of certain battles—surely there are too many zeros describing the numbers of those maimed or slaughtered in just one encounter?

No, sadly, the numbers are not typos.

Understandably, almost all history books focus on a relatively brief period. The more I read, the more I realized I wanted to find out the causes of the events which led to a specific conflict.

Any study of WWI eventually has to acknowledge how what happened in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, or the two Boer Wars at the end of the 19th century, or the Russo-Japanese War of 1905—to name but three of many—had a major effect of why the Great War was fought and where it was fought.

It is my assumption that today’s reader is largely ignorant about the wars which came before World War One. So, to give the necessary background, I made the decision to write about these earlier conflicts so that my readers can better appreciate why, for instance, France was so obsessed with the return of Alsace, or why Britain became so anxious at the German decision to create a navy to match the might of the Royal Navy.

But where to start such a narrative.

Well, I could start with Adam and Eve but that would mean I would never finish writing my tome. So I settled on starting with the defeat of Napoleon in 1814. This gives a nice round number to the years covered by most of my discussion: the century between Napoleon’s defeat and the start of WWI in 1914. But such bookends also make historical sense as Europe was relatively peaceful after the fall of Napoleon until one hundred years elapsed. Peaceful but hardly inactive.

I have done my best to document the tectonic plates of history which shifted and bumped until they finally crashed into each other with such force that the world’s first global war, one touching every continent including Antarctica, erupted with volcanic fury.

When devouring histories of the Great War and its predecessors, I frequently found myself starved for information about other aspects of daily life happening particularly when troops gathered in repose while on leave. What songs were popular? To what entertainments did they treat themselves (naughty or nice)?

I also craved information about the female characters whose pillow talk had so much influence over so many male policy-makers, yet whose influence is rarely discussed in histories of 19th and early 20th century warfare.

In fact, sex rarely raises its mug in martial and political histories of the Victorian and Edwardian eras, reflecting a strange prudery given the important of sex in human affairs.

Yet, then, as now, sex in all its manifestations was a primal driver of mankind’s behaviour, so, in my book, I do what I shed light on what is usually kept in the dark and out of sight, kept under the covers so to speak.

To sum up, since I could not find a book which gave me, in an accessible and entertaining manner, the social, political, and military history of those forces which came together to cause WWI, I decided to write my own book.

Additionally, I wanted a volume that contained lots of illustrations of people and places to help lay readers better understand what was described in the text. Furthermore, I wanted today’s reader to grasp how people during the war (and in the eras preceding it) saw the conflicts.

Most histories have only a few pages of black and white photos to complement their impressive amounts of prose. In contrast, I wanted a book full of images published at the same (or nearly the same) time as the events being described.

In other words, as much as possible I want today’s reader to see the world as the Victorians and Edwardians saw it. This meant they had a skewed vision of what was happening abroad, largely due to government censorship of what could be published. Moreover, because true colour photography was not invented until well after WWI, most people living in the years covered by my history, saw the world abroad mostly in black-and-white.

There was, though, an exception to this monochrome view of the world. Colour trading cards became popular in the 1870s and for several decades remained common as rewards inside packages of chocolate, meat extracts, tea, coffee, biscuits, and other edibles.

These cards were printed in the millions and covered a daunting rage of subjects, including foreign flora, fauna, and people as well as militaria.

Postcards became even more popular than trading cards a little later, starting in the 1890’s. They cover a vastly wider range of topics, and I have included hundreds of examples (often hand-tinted when first published) that give helpful illustration, I hope, to how people at the time perceived the politics and the wars so deeply affecting their lives.

As a result, my book contains well over a thousand images—the majority, by far, never published before in any book.