Books and Vintage Merchandise Store

Here are some Interesting Facts about Significant Places I reflect upon in my WWI Book.

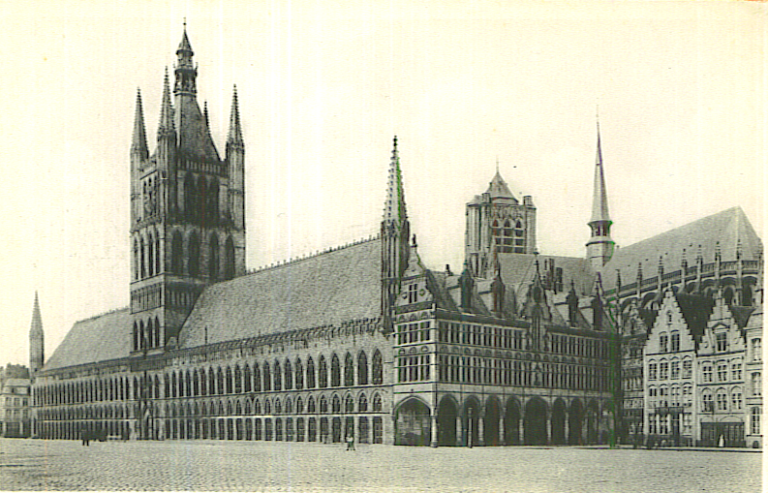

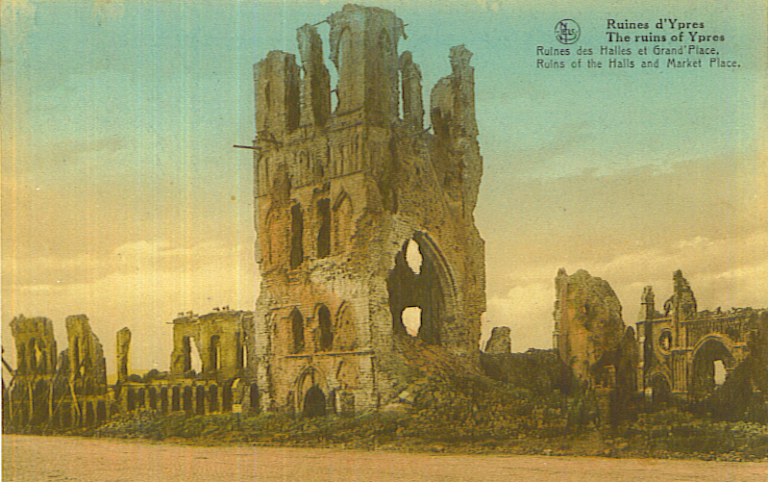

When it was completed ca 1300 the Cloth Hall in Ypres, Belgium was one of the biggest commercial buildings in the world, a medieval centre for cloth and wool merchants to conduct business with buyers from across Europe and the Middle East.

Unfortunately the height of the main tower made it a perfect target for German gunners who, for most of the war, fired from hilltops on three sides of the city.

The Cloth Hall stood proud and beautiful for over six hundred years—then was reduced by enemy shelling to piles of rubble within less than two years.

The Cloth Hall of Ypres photographed within days of the end of WWI.

At great financial cost, between 1933 and 1967, the Belgians rebuilt the entire building exactly as it had been.

Early 20th c German postcard of the Arminius Monument in the Teutoburg Forest dedicated to the first and only Germanic tribal leader to drive the Romans from what is now Germany.

As war with the Latin people of France and Italy erupted in 1914, Arminius became a handy symbol of German resistance to foreign domination.

The statue is unsubtle in its stance: Arminius brazenly faces France. An unmistakable engraving on his sword reads in German “Germans, our unity is my strength. And my strength is German power”.

Curiously, although Arminius is allegedly little celebrated in Germany in our time, somehow over half-a-million tourists visit this monument each year, making it one of the most popular attractions for holiday-goers in the entire country.

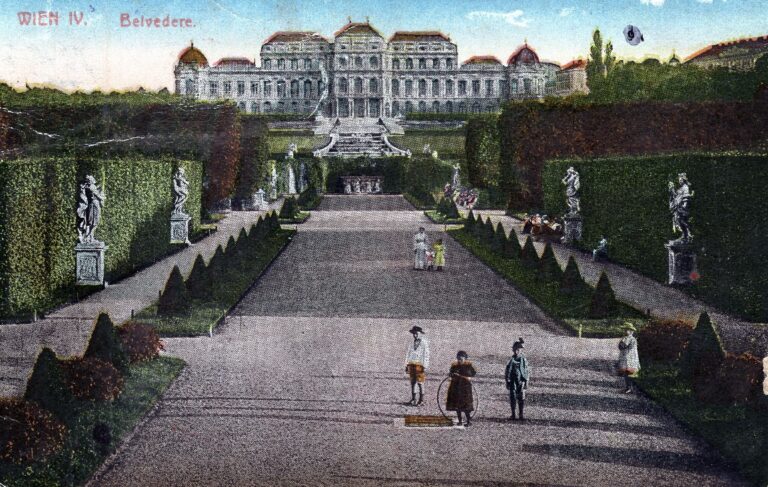

This magnificent palace sits just outside the centre of Vienna.

It was to here that Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his bride Countess Sophie moved shortly after their wedding.

Delightful as the home may appear, it was hell for the couple. Both the royal court of the Habsburgs and the high society of Austria regarded Sophie as of insufficient rank in nobility to be the wife of the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Sophie was endlessly humiliated via every trick of protocol known to the snobs and petty-minded of the capital.

Even when the couple held a large dinner in this palace, the enforcers of protocol made Sophie sit at the end of the long banquet table, far from her husband, with her chair almos halfway into the kitchen.

After a couple of years of this unapologetic social abuse, the newlyweds moved to a country palace–never to set foot here again.

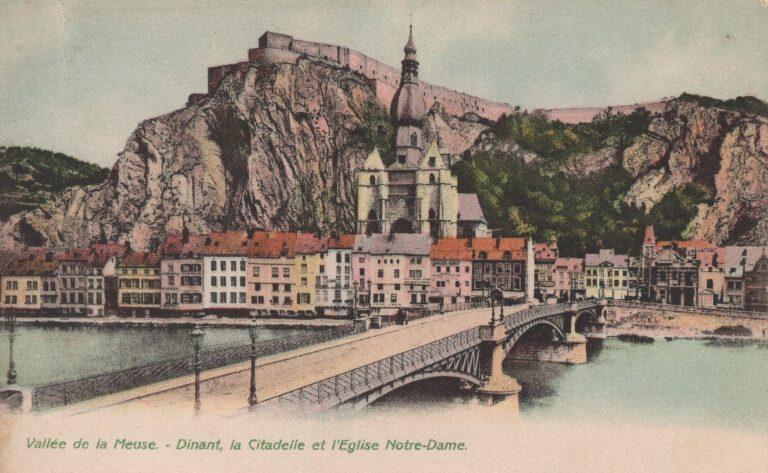

This pre-WWI postcard of Dinant, Belgium (a town of only a few thousand on the Meuse River) well illustrates why the locals regarded their citadel atop a gigantic rock as impregnable.

It was not. In the earliest days of WWI, the Germans easily drove the French army further west—one of the defenders seriously wounded in the battle, Charles de Gaulle, decades later became President of France.

Occupying German soldiers were convinced they occasionally came under rifle fire from local civilians.

To end this harassment, the German commander ordered the entire populace to gather in the main square. He chose 674 residents at random and had them shot dead in front of their horrified neighbours.

The youngest victim was three weeks old. Then, for good measure, he ordered a thousand buildings set ablaze, including every structure seen in this image.

For several decades up to WWI the well-to-do would stroll on foot (or ride in carriages at a walking pace) up and down the main thoroughfare of the Bois de Boulogne, a huge park on the western edge of Paris.

This was not done for physical exercise. Women wore their finest clothes and carefully, sometimes cattily, remarked to their friends on the fashions worn by their contemporaries.

The highest-priced courtesans would flaunt their immense wealth by wearing impossibly expensive gowns made by the finest couturiers, as their grandly ornate carriages were pulled behind teams or six white horses.

Men would anxiously await a tip of the hate from a superior passing in the opposite direction, hoping this meant they might soon rise in station or be invited to a banquet previously beyond their dreams. People who had fallen in social favour were ostentatiously snubbed, their existence not even acknowledged by a smile or even a nod.

The general public, after attending church, would sometimes stand on the sidelines of this parade to gawk in wonder (or rage) at these comfortable displays of wealth and advantage.

Sylvan scenes such as this were destroyed once WWI began and Zeppelin bombs and long-range artillery made promenades like this suicidal.

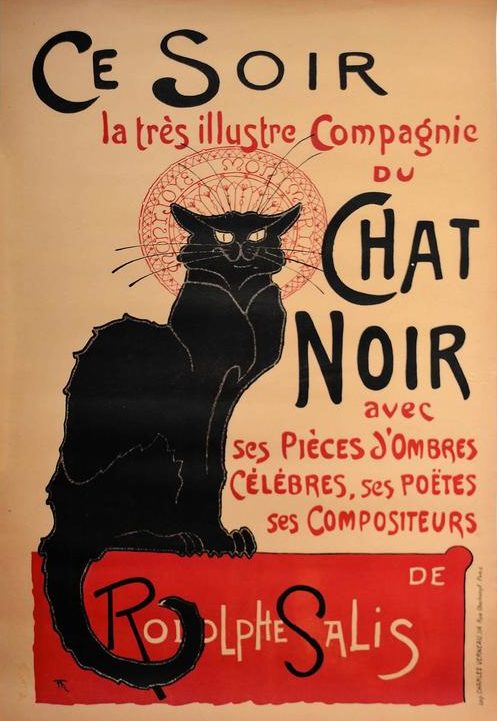

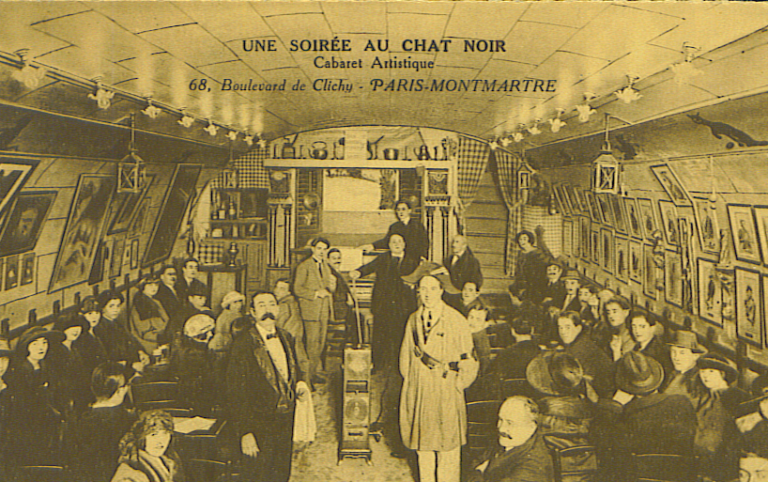

Intimate nightclubs which sometimes presented musical or variety acts (incuding magic lantern slide-shows) were especially popular in Paris from the 1880s onwards.

One of the reasons the French capital was so rich in artistic life was that young impoverished authors, painters, composers and other bohemians could gather in such venues, spend an evening discussing aesthetics with friends, and not have to spend much money.

This is an unusual interior photo postcard of the earliest and most famous of these cabarets, Le Chat Noir (The Black Cat). Its owner was astute enough to publish a weekly journal filled with news about rising stars of the arts as well as examples of their work, thereby reinforcing the club’s reputation as a meeting place of the best young artists.